Research by the Hintalovon Child Rights Foundation on the social acceptance of child abuse and the opportunities in community-based child safeguarding

Although protection of children against violence is a returning topic in public discourse, it is only given more attention when tragedy strikes. When this happens, we tend to focus on responsibility, mistakes and failures. However, we must recognize that protecting children is a shared responsibility of our society. In order to support them as effectively as possible, we have undertaken a comprehensive research to understand children’s and adults’ knowledge and views on violence. At the initiative of the Hintalovon Child Rights Foundation, non-profit organisations from four other countries – Albania, Moldova, Romania and Slovakia – participated in the research to gain a comprehensive picture of the perception of child abuse in the region. Child Rights Center Albania, Albania, Concordia, Moldova, Caritas Alba Iulia, Romania, OBČIANSKE ZDRUŽENIE FutuReg, Slovakia were our partner organisation in the research. We present first the Hungarian results.

In the research, we were seeking answers to the questions:

- What information children and adults have about abuse?

- What do they think about violence?

- Where do they get their information?

- Do they know where to turn to if they experience abuse?

- Who do they think is responsible for handling these cases?

- Which communities do they feel more responsible for and

- Which would take stronger actions against violence?

The research was composed of three parts: an online questionnaire for adults, which received more than 10,000 responses, a focus group survey of a local community and a three-part online questionnaire for children, which received more than 1,400 responses.

Results

One of the key findings of the research, which is essential when designing a community-based child safeguarding programme, is the significant contrast between the intense interest and sensitivity to the issue of violence against children and the passivity. While the number of responses (10,887) to the online questionnaires was record high, the focus group part (which required more commitment, as it took more time) was less interesting, and it was difficult to recruit participants. The contrast was also reflected in the finding showing there was a demand from the public for more information on the topic, but focus group participants sometimes experienced lack of interest in the informative programmes available. The lack of knowledge is a barrier to identifying abuse and to act against it.

Knowledge protects, lack of knowledge leaves you vulnerable

Based on the findings of the research, there is full consensus that sexual abuse, serious physical abuse and neglect causing serious health problems are unacceptable forms of violance against children. However, less serious physical abuse (e.g. slapping), or verbal abuse were found to be more tolerated.

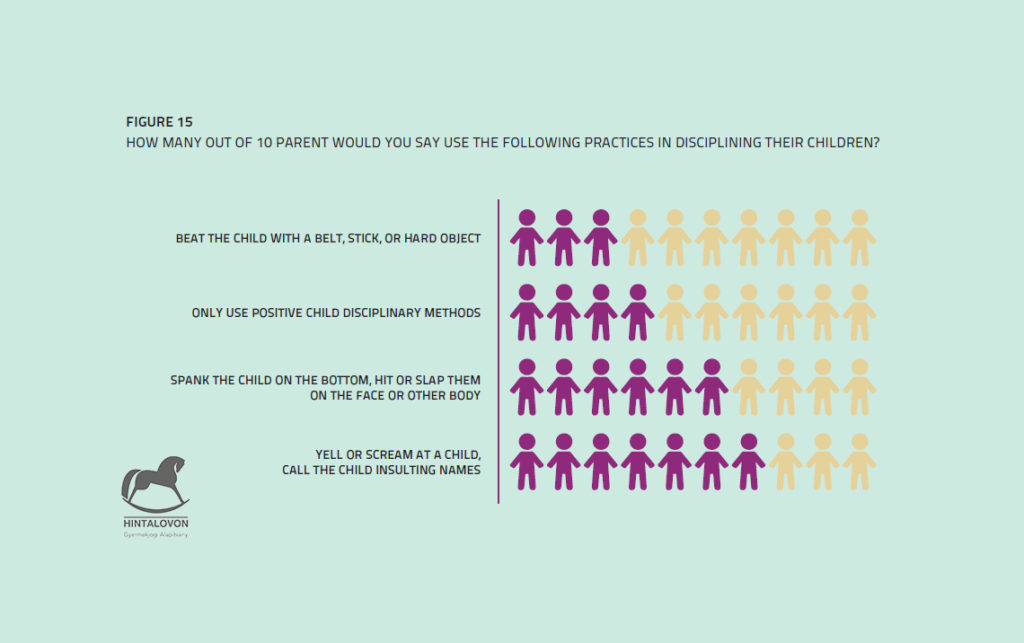

Around a quarter of respondents either fully or partially agreed that physical punishment of children is not good but sometimes inevitable. 15% believe that parents have the right to hit their child if it is important that the child does not repeat a certain behaviour. According to the respondents, in Hungary, 6 out of 10 parents use physical punishment and 70% think that people do not show interest when they see a parent slap their child. Verbal abuse (e.g. shouting, shaming) was considered the least violent. Furthermore, it was also perceived to be a common occurrence in society, with 7 out of 10 parents using verbal abuse as a form of discipline. A greater acceptance of verbal abuse was also reflected in the responses of the child survey – in these cases children did nothing, or did not talk about it because they did not think it was a significant problem.

Child rights ambassadors also confirmed that their generation has a high level of threshold for stimulus and recognises abuse in fewer situations than it happens. Children are mainly exposed to information about serious violence (e.g sexual abuse), and this leads to acceptance or lack of awareness of less serious violence. In conversations with adults or other information channels, they receive less information about what to do in more ordinary situations.

Least said, soonest mended

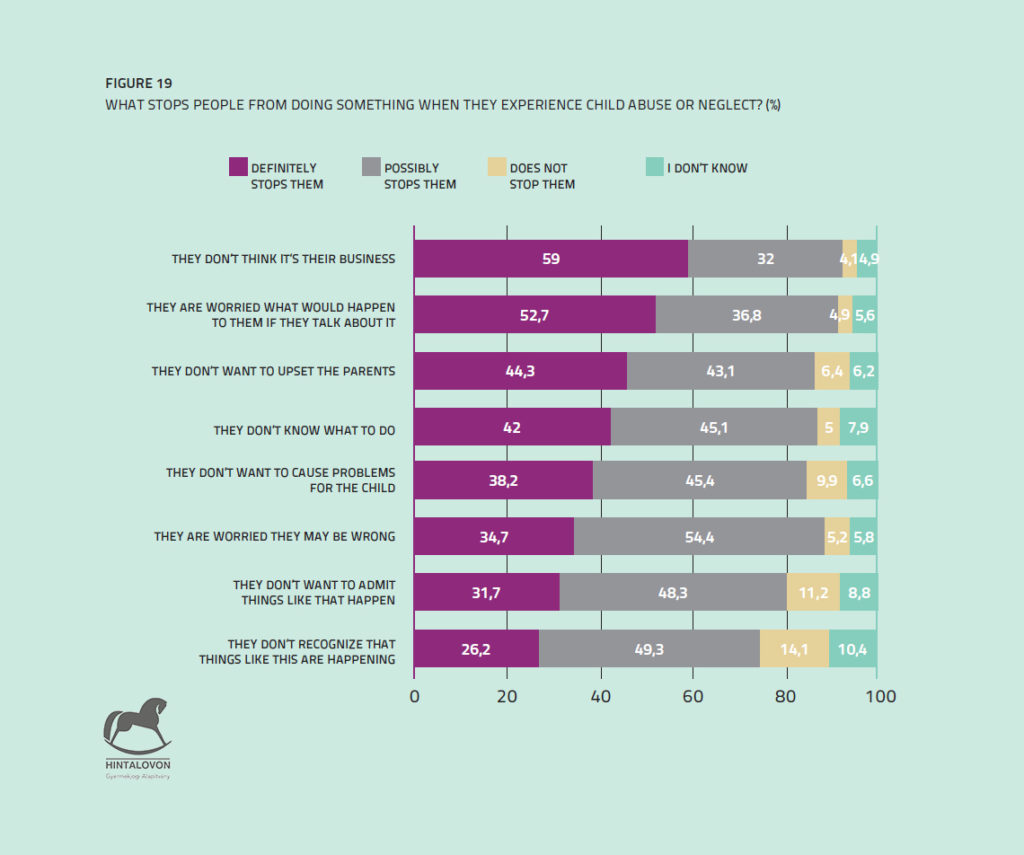

9 answers out of 10 respondents agree that all members of a community have the responsibility to protect children and that parents should not discipline their child solely as they see fit. However, in their opinion on average only 2 out of 10 adults would intervene or call the authorities if they witnessed violence against a child. It is important to underline that the main obstacles to reporting – notifying the authorities or a competent expert- or intervening are people’s passivity (60%) and their own protection (53% are worried what will happen to them if they speak up). Avoiding making a mistake or getting the child in trouble was only identified as a possible obstacle.

This was also confirmed by the findings of the focus group, with participating parents also agreeing that people do not want to get in trouble because of this. Firstly, they fear negative consequences if they “intervene”, secondly, if the reaction is inappropriate, they would cause a worse situation in the family concerned. According to child protection professionals, in most cases people do not have enough information about being protected by confidentiality obligations in case of a report. However, if they do know, they fear being identified in a close-knit community and being judged for their intervention.

These fears were reported to be felt not only by people in general but also by other professionals working with children, such as teachers. According to parents, people only dare to intervene in communities where relationships are strong and members know each other well. In cities, this does not necessarily coincide with neighbourhoods. In this respect, parent communities organised around children, such as friendships between parents of children attending the same kindergarten or school, seem to be more effective. This type of community can develop on the playground, where parents spend long hours with their children.

Children feel powerless against adults

Empowering communities is also important because most children will come forward against an offender their own age. They feel powerless in the face of adults and assume less conflict, as confirmed by the child rights ambassadors. They only engage in conflict with adults if they have sufficient information about what they can do in these cases. The research shows that they tell other adults, mainly their parents, about abuse by an adult, and their friends about abuse by another child. They seek help from professionals (e.g. psychologist, psychological support) when it is very difficult to share the stories with others

The results show well that there is a significant lack of information on child protection among the adult population. It is noteworthy that only half of the respondents assumed that the law requires everyone to report violence against children, and 10% were not aware that such a law exists. However, the majority of respondents knew that children can report cases of abuse, 30% had no idea what options children have in such cases.

Lack of education, lack of support networks

However, the transfer of child protection information proves to be difficult. The results of the focus groups show that traditional ways of disseminating information (e.g. leaflets, awareness-raising presentations?) often fail to achieve the intended purpose. According to parents and professionals, improving the relationship between professionals and the public would support the development of community-based child safeguarding, e.g. by way of regular informal programmes where professionals and parents could meet. On the one hand, it is important that these programmes are held on a regular basis, and on the other hand, it is important that they do not create a burden for parents, as this may prevent them from coming back to subsequent meetings. Providing other services could be useful to motivate them to attend, e.g. it may be important to organize babysitting for the younger children. Local governments would be primarily responsible for organising such events: they would finance the programmes and take care of the main organisational tasks. In addition to local governments, parental communities could also play an important role, for example in promoting these events to the other parents and in building active relationships between professionals and parents. They have specific information on child protection that they can share with other parents.

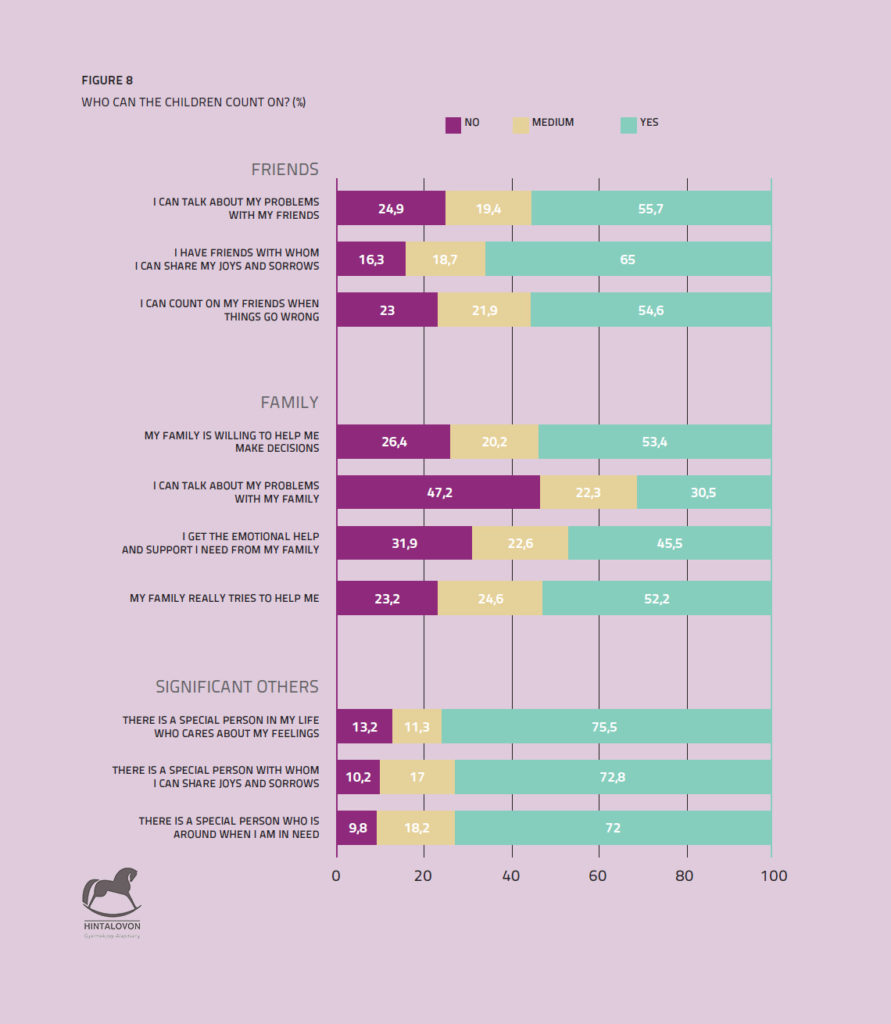

Treating children as partners is key to implementing community-based child safeguarding. Experts participating in the focus group stressed the importance of building a well-organised peer network, as the findings of the child survey show that children tend to share their problems with friends rather than family.

Key Findings

Violence is not acceptable, but it is present: 9 out of 10 respondents say that parents who use physical discipline cannot be excused, even if they are upset. In contrast, 6 out of 10 parents use spanking, hitting or slapping, according to the respondents.

Children are left alone: one in ten children think that their environment is not helpful enough. Responding children felt more supported by their friends than their family, and found it harder to turn to their family than to their friends.

Almost everyone recognises the responsibility of the community, but 6 out of 10 adults think it is not their job to intervene. 9 out of 10 respondents think it is the responsibility of all members of the community to protect children, with parents and professionals working together and listening to children’s signals and requests for help. Almost everyone agrees that protecting children is a shared responsibility, yet 6 out of 10 adults think it is not their job to intervene when a child is being abused.

Other important findings, data

- Many cases remain hidden because the environment either does not recognise the abuse or does not intervene.

- 62% of respondents say abuse is a serious problem, 30% say it is a problem, but there are more serious problems. 4% do not consider it a problem at all.

- Almost half of the respondents only assume that there is a law requiring to report child abuse.

- Parents’ discipline methods are most influenced by the spouse/partner.

- 21.8% of men agree that it is worse to hit a girl than a boy, while only 5% of women think the same.

- The majority see physical punishment the most acceptable in situations when their own behaviour endangers the child, such as running across a busy road, stealing something, or smoking, drinking alcohol or taking drugs, skipping school or hitting another child.

- According to 8 out of 10 adults, slapping or spanking is not an effective parenting method.

- 13% of adults think it is wrong not to use physical or psychological punishment when raising children.

- A third of adults think their environment expects them to punish their child if they misbehave.

- The vast majority of respondents do not consider it acceptable that they or someone else would hit their child.Those who would give permission to others to do so would primarily allow adult family members (10.5%).

- According to respondents, 2 out of 10 adults would intervene if they witnessed child abuse.

- 59% of respondents consider it is not their job to intervene, 52.7% are being worried about what will happen to them if they talk about, 44.3% does not want to upset the parents of the children.

- Identifying the person who makes the report is a problem in a small community as it is difficult to effectively establish confidentiality in a community where people know each other.

- Children are better able to stand up for themselves if they have discussed before what to do in such situations.

- The responses show that information about serious abuse is more accessible to the children. They are less aware of everyday situations (verbal aggression in the street, peer bullying).

- Children are much more likely to stand up for themselves when they are confronted with their peers, it is much more difficult to “get into a conflict” with an adult, either known or unknown.

Methodology of the research

The research was composed of three parts: an online questionnaire for adults, a focus group survey of a local community and a three-part online questionnaire for children. This research report will present the main findings. We will use these findings to develop guidelines to support child protection in local communities. Each of the sections can be considered as independent research, but they also reinforce each other.

- One slap is not the end of the world? – Questionnaire for adults on violence against children

The online questionnaire was open to adults over the age of 18, regardless of whether or not they have children. Our approach in this part of the research was that all members of the society have a responsibility to prevent violence against children. The aim of the online questionnaire was to find out how people in Hungary feel about violence against children, how much they know about it and where they get their information. We also wanted to know who they think is responsible for preventing and dealing with violence against children, are there groups that are more committed to the issue? The questionnaire received more than 10,000 responses.

- Responsibility for child protection in communities – Focus group research in a local community

Understanding how smaller communities can protect children against violence was essential in identifying child protection opportunities at the community level. We were curious how well the members of a residential community are connected to each other and what they think about the protection of children in their community. Who is responsible for child safety at the local level? What problems do they face in their community that threaten the safety of children? What solutions do they have? What do they think about their personal responsibility? The focus groups were conducted with a team of 9 people, including parents and professionals.

- How do you see it? – Questionnaire for children on abuse

Understanding children’s views is essential in developing a child protection programme. That is why we wanted to find out how they behave in situations of abuse. Do they dare to act? How do they know what to do? Where do they turn to for help? With whom do they share what has happened? In general, what do they think about how supportive adults in their environment are? The online survey sought answers to these questions among children aged 13-17, based on 1410 responses.